Overview

A WebXR application bringing Vision Pro-style spatial UI paradigms to live TV streaming across VR and AR headsets, built using open web technologies and the DVB-I broadcast standard.

Background

As part of my Advanced Web Technologies project at TU Berlin, we were tasked with building a production web application using modern technologies not typically found on most websites. The Apple Vision Pro had just launched in the United States, and my group and I wanted to explore how the user interface paradigms Apple designed would translate to open-source web technologies. This meant we could bring spatial computing experiences to platforms beyond Apple’s ecosystem, including headsets that don’t even have traditional non-game app stores available, like many SteamVR devices.

We designed and implemented a TV-watching app using the DVB-I standard, which we had previously learned about in our coursework.

Our Approach

Feasibility Study

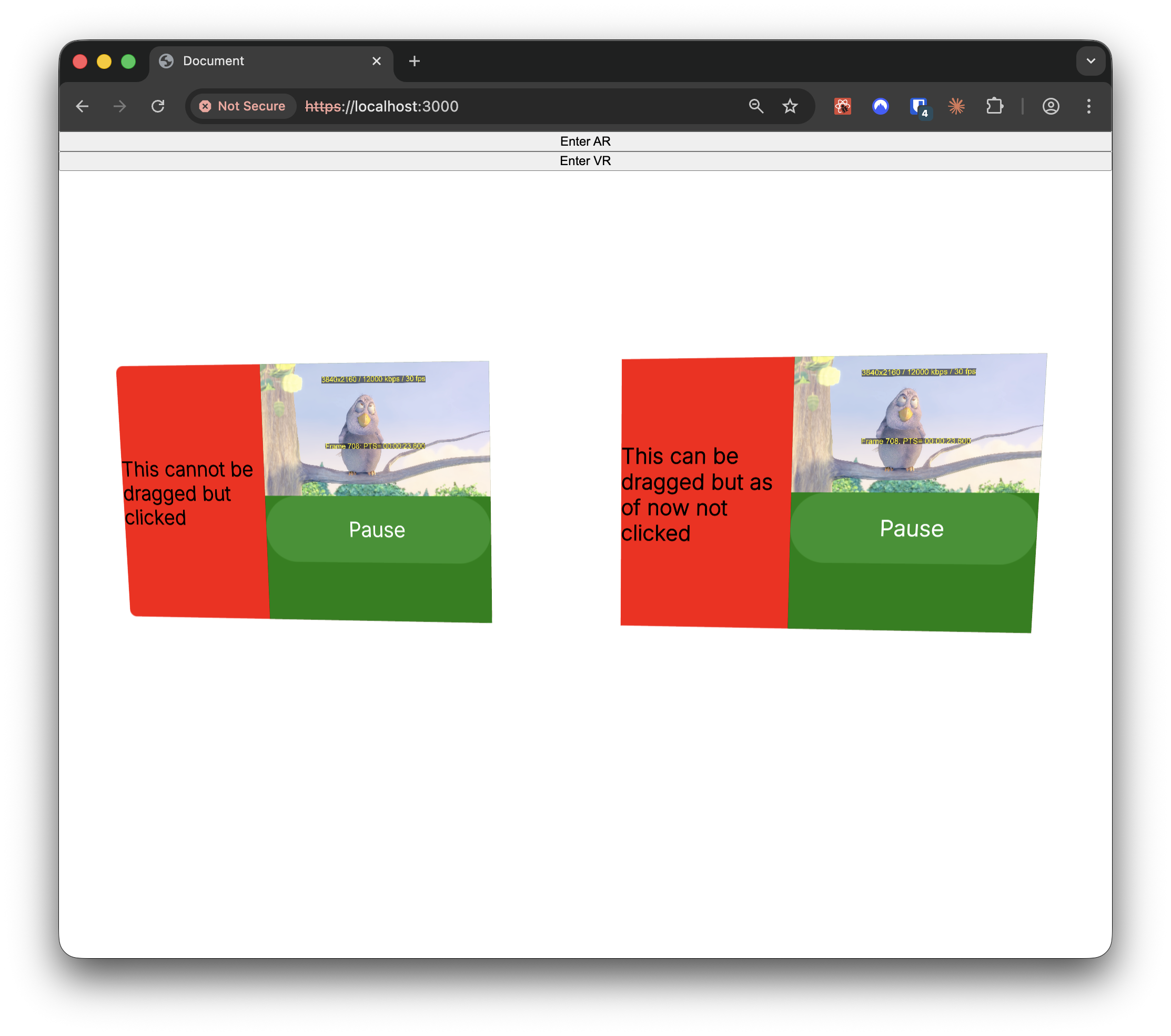

To kick off the project, we implemented a simple feasibility study on web-based video playback in XR, just streaming a test video to a floating player. Satisfied with the playback performance, we felt confident we could deliver the project and began production.

UI Design

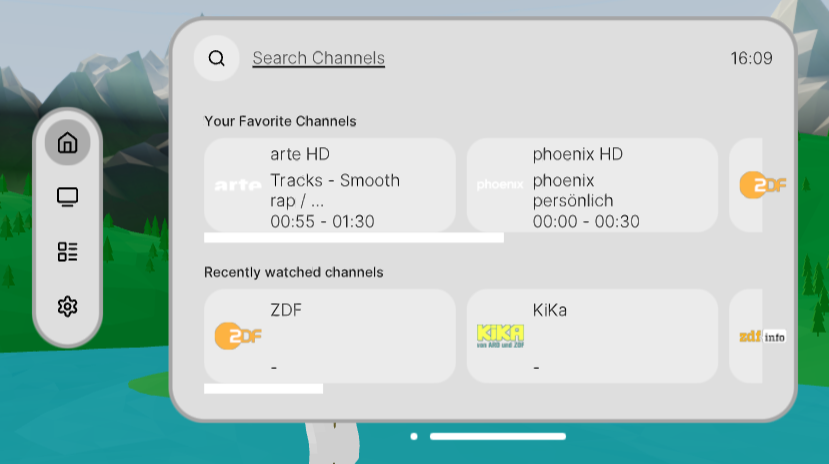

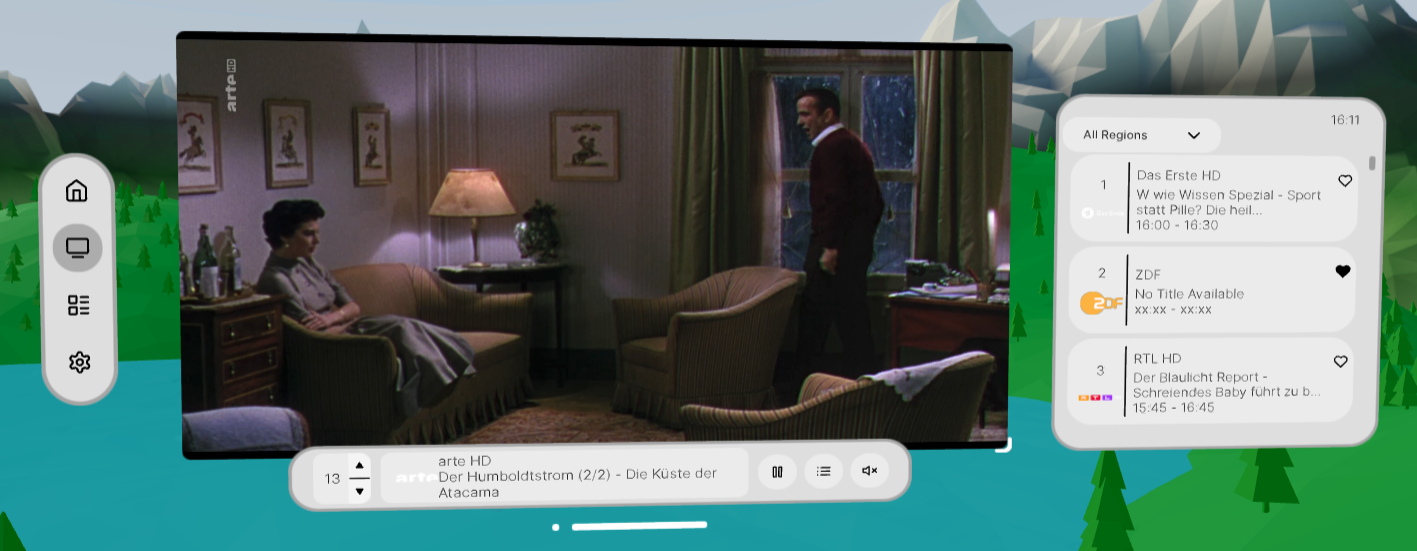

Our next step was designing the user experience. We created design mockups in Figma, planning for a fully-featured TV experience including a channel guide and the ability to save channels. We wanted to leverage the strengths of XR: resizable and movable UI elements, multiple floating windows instead of one monolithic 2D interface, and the choice between full immersion in a 3D environment and passthrough mode.

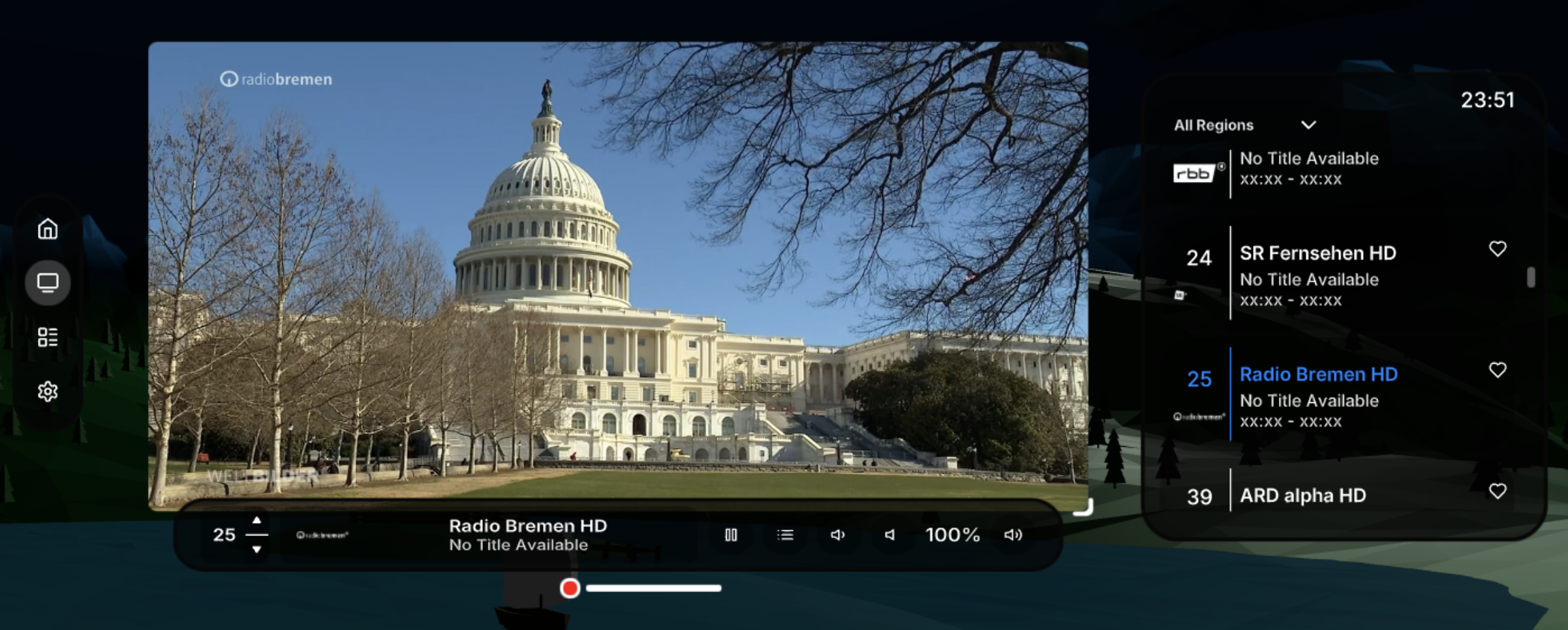

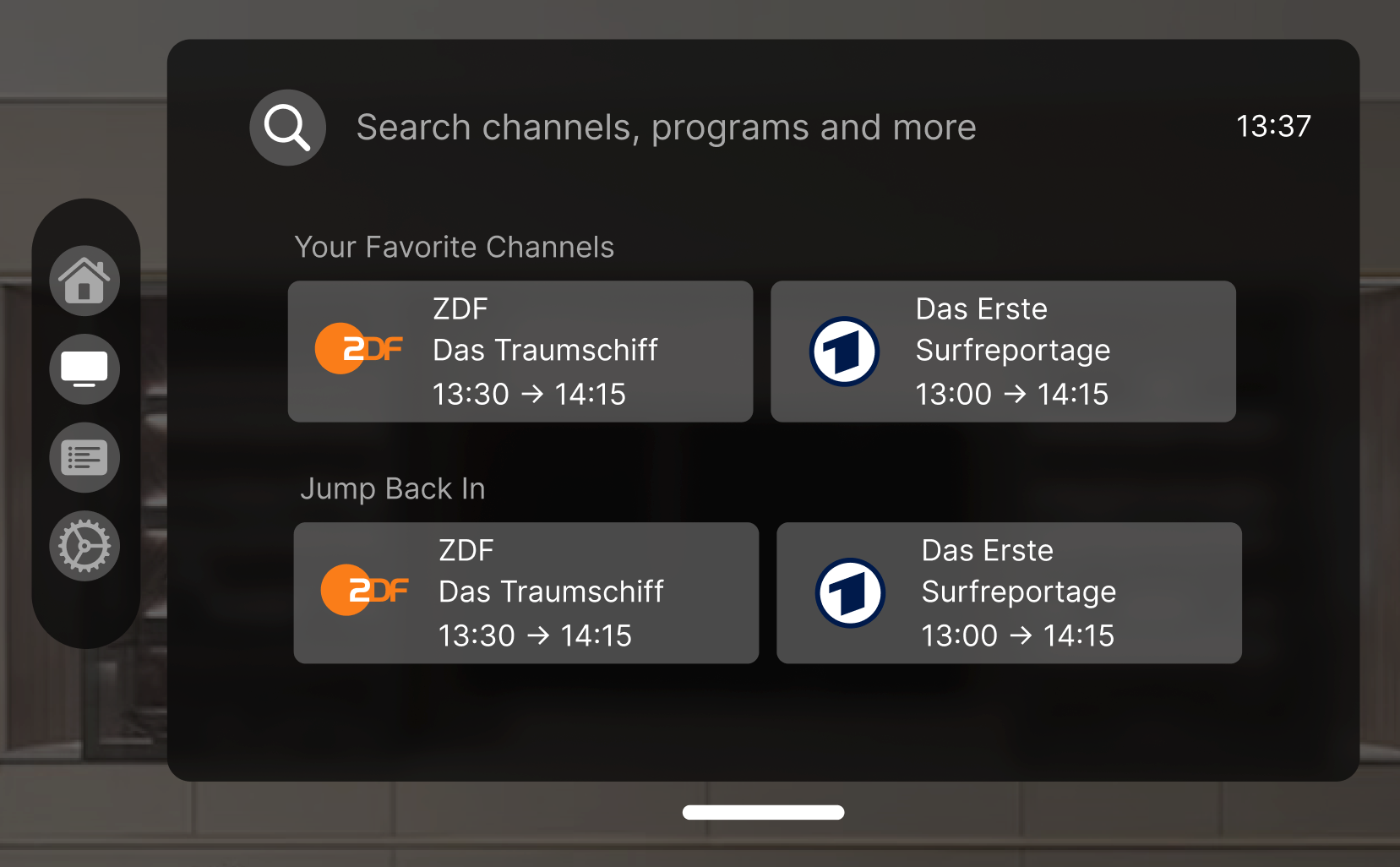

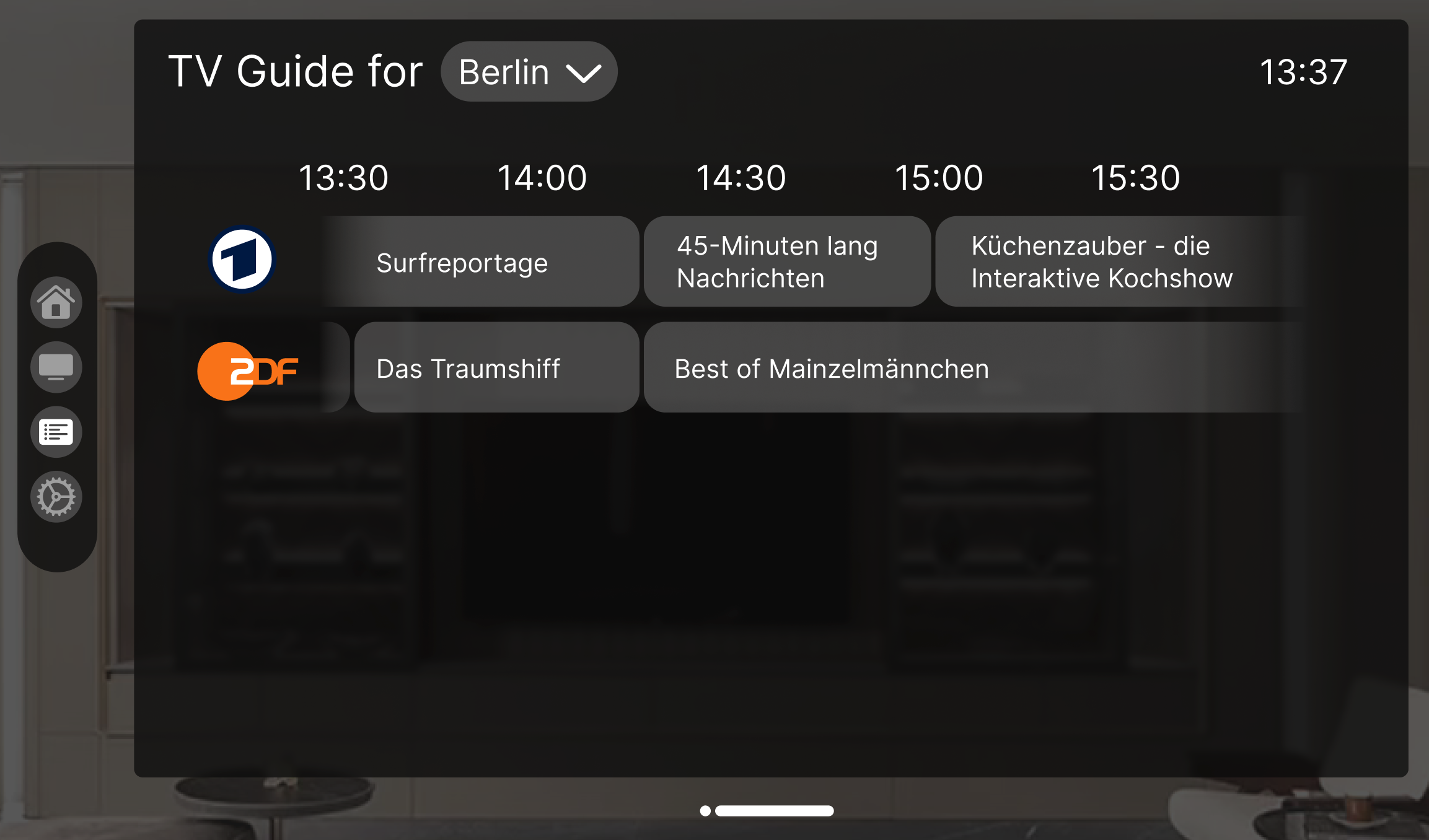

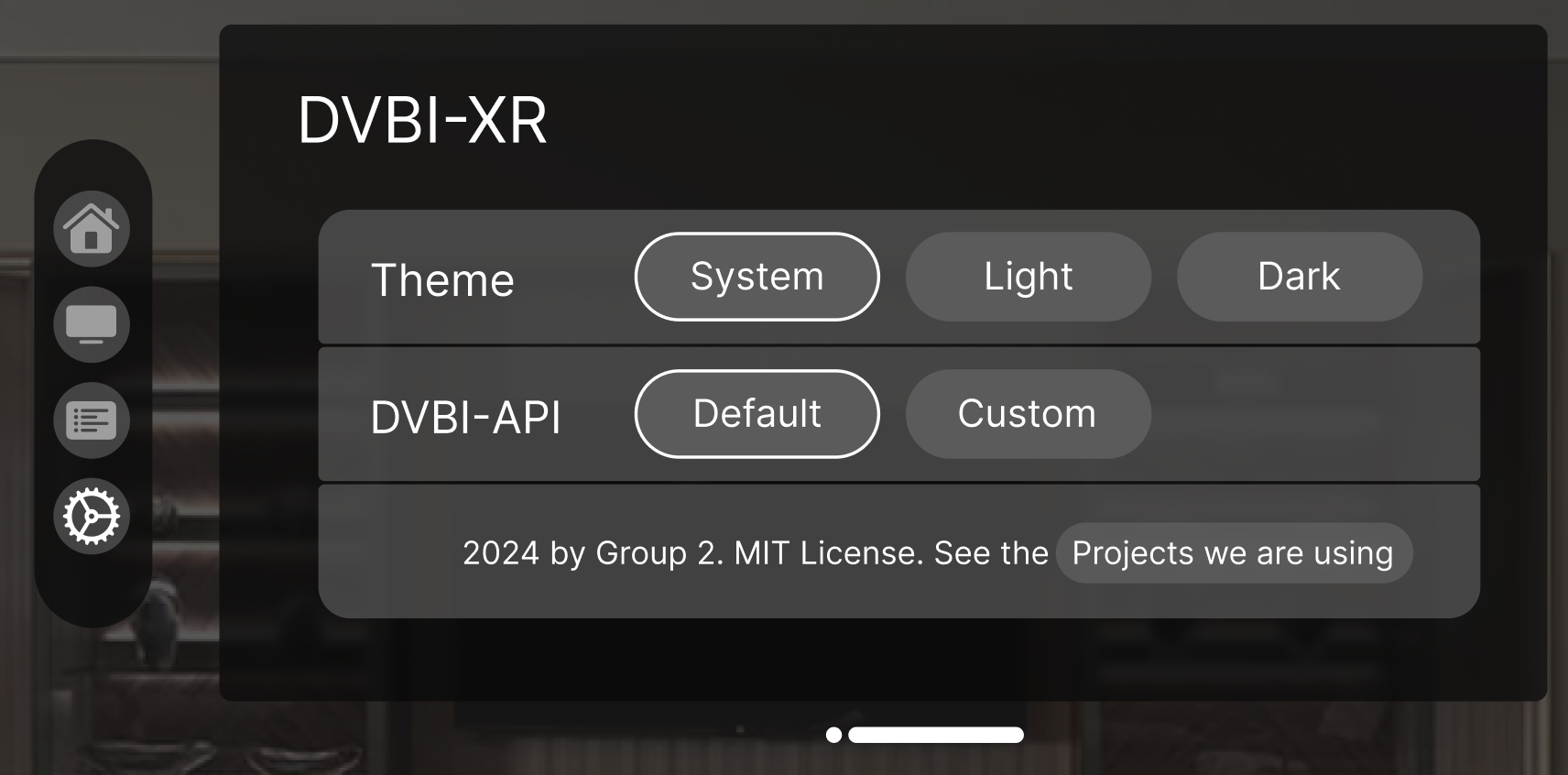

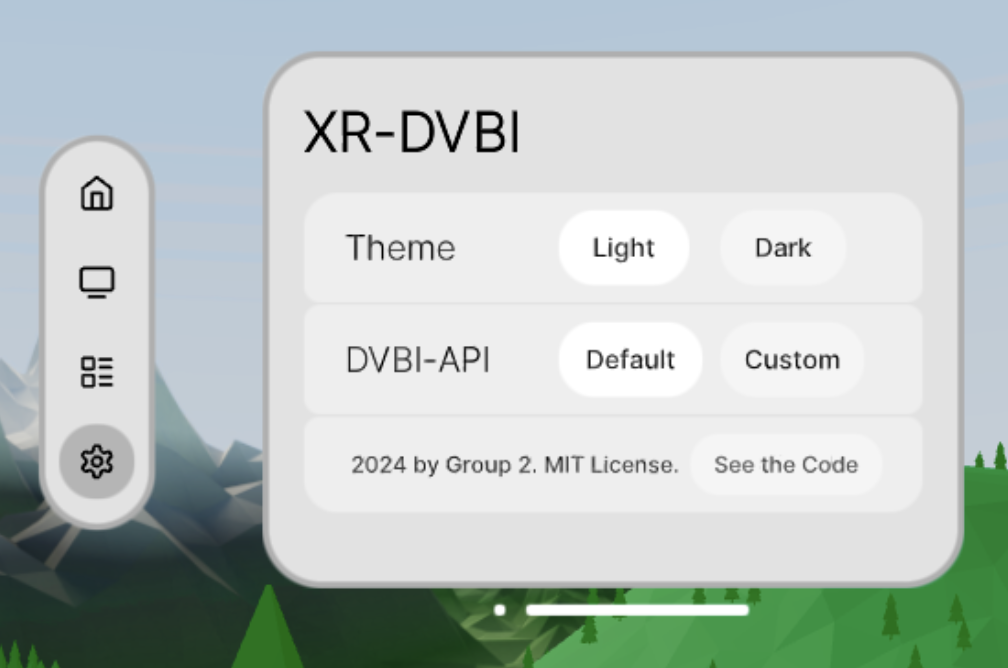

The design consists of four main screens: Home for recent and liked channels, TV App as the main viewing screen with a channel list on the side, Channel Guide to browse available programming, and Settings for app configuration.

Users navigate between these screens using a navigation sub-window on the side. 3D window management is handled through a familiar smartphone-style “home bar” that lets users reposition the floating window arrangement.

Technology Stack

We researched our options, which came down to A-Frame versus Three.js-based approaches. A-Frame is specialized for VR, while Three.js is a general-purpose WebGL library. We decided on Three.js, primarily because of the maturity of the platform, and the availability of pre-styled UI components through uikit.

We also chose React, since we’d be building many components that we could design independently within our team and assemble later using props and Zustand for global state management. To facilitate this workflow, we used Storybook, which allowed us to create pre-defined scenes for testing individual components or sub-assemblies in isolation.

Team Organization

We coordinated through biweekly meetings and a central Kanban board where we tracked todos and implementation status. Code was hosted on GitHub. Since we had fixed deadlines for the initial design, first working prototype, and final product, we decided against Agile continuous deployment and instead used a more traditional waterfall model. We started each sprint by defining our goals, discussing architecture, and then splitting up tasks. Toward the end of each sprint, we stayed in closer contact and made ourselves available for questions from teammates.

Implementation

We had two main tasks: integrating DVB-I and building the 3D interface.

DVB-I Integration

Working with DVB-I proved challenging because the data was inconsistent. We used the DVB-I spec to understand the structure, then verified against actual API output. The problem was that we couldn’t rely on fields being available and containing data as described in the official documentation. For every field we wanted to use, we had to manually check our data to verify it existed, and sometimes the data we needed was in a completely different field than the spec indicated. This meant a lot of defensive coding and fallback logic.

3D Environment and Interface

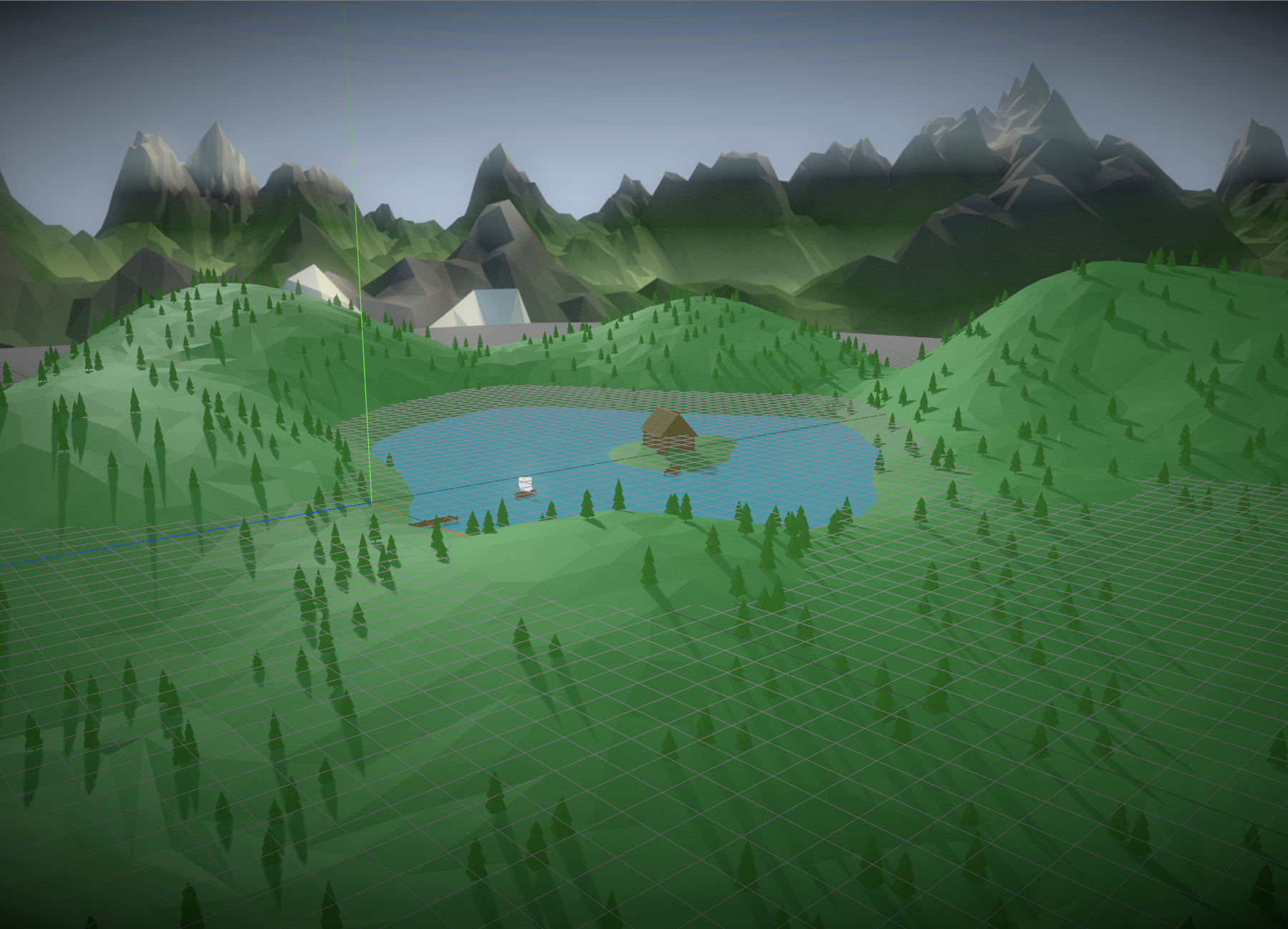

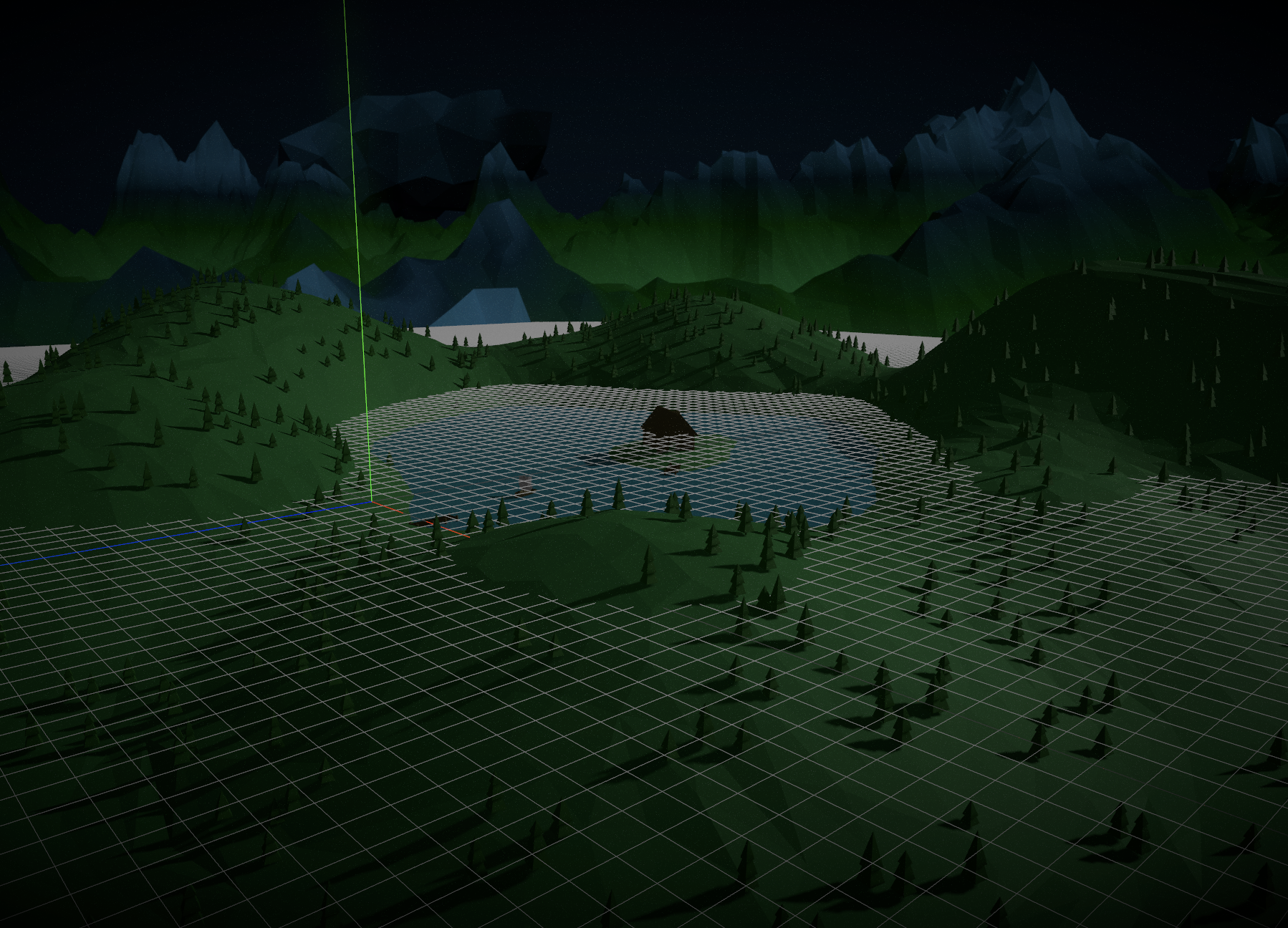

The app features a low-poly lakeside environment with a TV screen and floating interface elements above the water. We created day and night versions, with dynamic lighting that actually comes from the rendered sun and moon positions in the scene.

Users interact via controllers, primarily using clicking and dragging with the triggers to manipulate windows and navigate the interface. The difference between AR and VR modes is significant: in AR, users see camera passthrough of their real environment with UI elements overlaid (no 3D environment rendered), while VR renders the full lakeside environment.

The final implementation includes all the screens from our initial design. Window management is handled through the home bar interface, and we implemented light and dark modes for both the UI and the 3D environment.

During development, we made a few practical adjustments. The collapsible volume slider was replaced with button controls—they proved much more reliable for VR controller interactions. We also had to remove the subtitles feature, as the DVB-I feeds rarely included subtitle data in practice.

Collaboration was straightforward once we’d agreed on the technology stack. We split up the components and verified they worked using Storybook, which also served as documentation for when we assembled everything together. My colleague Fiete worked on the DASH player, while I focused on the 3D aspects, like implementing the environment and creating its day and night variations.

Challenges

Initially, we wanted to use Three.js’s HTML tag for complex elements like the channel guide. This worked fine in the VR simulator, but then didn’t show up in actual VR. We learned that HTML isn’t supported in VR, but this didn’t surface in the emulator because it’s not actually rendering in VR mode. We had to rebuild these elements using native 3D UI components.

There were CORS problems fetching the channel’s preview images from their hosted locations in the DVB-I data. As a workaround, we wrote a script to fetch these images once and store cached versions in our assets. When a CORS problem occurred, we’d fall back to the cached image if we had it.

We also hit a dependency issue at the worst possible time. The component library changed under our feet near the end of the project. The team had uploaded a new version and deleted files on a backend server necessary for the old version to work. As a result, we had to scramble to verify and if needed update all components to work with the new version, which made the final stretch more stressful than it needed to be.

Results

We presented our results and demonstrated the app at Fraunhofer FOKUS. The reception was generally positive. The app proved usable by novice users without explanation, and features like the channel guide and AR/VR switching were well received.

Performance was good but not perfect on an Oculus Quest Pro, which tracks with other web apps on that platform. Unfortunately, we didn’t have a more powerful headset like a PCVR-based one on hand to test with.

It would have been nice to integrate more deeply with the OS in our application, such as delegating window management to the OS, and allowing our app to run alongside other applications. Ideally, the user would be able to pin the TV application to one location in their environment, while pinning things like a weather widget or work-related applications in another place. Since WebXR applications cannot coexist with other software in 3D space, however, this was unfortunately not possible.

Takeaways

The project demonstrated that web-based VR media experiences are viable, and the spatial interface paradigm translates well across platforms. What’s particularly nice is that the same codebase runs on vastly different headsets without modification.

That said, we had to put in more work than if we’d developed natively for Vision Pro. While we had a UI library available, it’s not as mature as something like SwiftUI. As already mentioned, the chosen approach also inhibited interplay with other installed apps.

For this reason, I believe that as the XR ecosystem matures, native cross-platform tools like React Native are a more promising approach than relying on as-of-now limited web-based solutions.

Personally however, it was a fun project working with less frequently used technology, and working in a team on a real app was a nice opportunity as part of my degree. This was definitely one of the modules that made me glad to have chosen TU Berlin for my masters!